by Briallen Hopper, Killing the Buddha

Three days before Michael Brown was shot and killed in Ferguson, Missouri, an advice column in The Village Voice went viral. A man who called himself “Son of a Right Winger” had written in with a problem: “I just can’t deal with my father anymore. He’s a 65-year-old super right-wing conservative who has basically turned into a total asshole intent on ruining our relationship and our planet with his politics.” The man explained that arguing didn’t get anywhere, but silence wasn’t a solution either: “When I try to spend time with him without talking politics or discussing any current events, there’s still an underlying tension that makes it really uncomfortable. Don’t get me wrong, I love him no matter what, but how do I explain to him that his politics are turning him into a monster, destroying the environment, and pushing away the people who care about him?”

The musician and advice columnist Andrew W.K. wrote a simple, earnest reply that has been shared on Facebook 218,000 times. After admonishing the man to see his father as a human being, he asserted that the real problem was not human-made global warming but political disagreement itself: “The world isn’t being destroyed by Democrats or Republicans, red or blue, liberal or conservative, religious or atheist—the world is being destroyed by one side believing the other side is destroying the world.” He pointed out the pointlessness of politics: “even the most noble efforts to organize the world are essentially futile.” He warned that “unrest, disagreement, resentment, and anger” are a dangerous distraction. And he cautioned against political self-confidence: “Have the strength to doubt and question what you believe as easily as you’re so quick to doubt his beliefs. … Don’t feel the need to always pick a side.”

I hated Andrew W.K.’s response, even though (like the almost quarter of a million people who shared it) I found a lot to agree with in it. I have a 63-year-old father with whom I deeply disagree about LGBT issues and abortion, and I still love him, respect him, and learn from him. My friendships with people across the political spectrum are important to me. And it’s hard to argue with Andrew W.K. when he says that that no one is perfect; politics are complicated; we should see each other as persons, not monsters; and love should be able to bridge barriers.

More than anything, though, what struck me about Andrew W.K.’s response was how white it was.

I don’t know anything about Andrew W.K.’s background beyond what an Internet search can tell me, but as a white American I do know this: It is a privilege to experience political differences as differences of opinion rather than differences of power. It is a privilege to be able to view all political issues in indistinguishable shades of gray. And, as I’ve been realizing in the month since Michael Brown’s death: It is a privilege when loving your political enemy means loving your father, not loving the man who killed your son—or the man who killed someone who might have been your son, or who might have been you.

I teach Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” four times a year to my students at Yale. I’ve taught it seventeen times now, and at this point certain passages live in my memory. When I first read the Village Voice column on my Facebook feed I couldn’t help but hear Andrew W.K. as one of King’s interlocutors—the well-meaning white moderates who said “settle down!” and “wait.” I imagined what Andrew W.K. might have written to King, who was an avowed believer in creating crises and fostering tension, and who was in the midst of a bitter conflict that both argument and silence had failed to resolve. And I wondered how he would respond to the furious people in Ferguson as they lifted their voices and faced tear gas and tanks to protest the latest instance of an unarmed black person killed by a white cop who would likely never be brought to justice. Maybe, like the white clergy King was responding to in 1963, Andrew W.K. would see the real problem as the “unrest” of the controversial protestors themselves, not the systemic injustice they were protesting. Maybe he would advise protestors in Birmingham or Ferguson, “The world isn’t being destroyed by racism—the world is being destroyed by non-violent protestors believing that racism is destroying the world.” Or, “Even the most noble efforts to organize the world are essentially futile.” Or, “Don’t feel the need to always pick a side.”

Of course, “Son of a Right Winger” is not Martin Luther King, Jr. Neither is he a teenager who needs to navigate his own neighborhood in a constant state of hyper-vigilance. He is merely a private person with political opinions and family problems. The stakes are different for him. Yes, he feels that the fate of the planet is hanging in the balance, but in his everyday life political issues impinge on him because they affect his relationship with his dad, not because they threaten his personal safety or access to jobs or justice. But this discrepancy is exactly my point.

The enthusiastic response to Andrew W.K.’s article doubtless speaks to some likeable qualities in the citizens of Facebook: our recognition of our common humanity with people who disagree with us (or at least with people who disagree with us and are also related to us), and our desire for closer relationships with them. But it also speaks to the desire of so many of us privileged people to avoid all tension and conflict while still feeling like we are a force for good in the world. It’s a way of letting ourselves off the hook; of lulling ourselves into inaction by making neutrality into a positive good.

According to Andrew W.K., we don’t need to challenge our friends and family on the things that matter to the planet or to our less privileged neighbors: In fact, we probably shouldn’t. We can even label this evasion “love.” And we don’t need to sacrifice anything for our political beliefs—not our lives, not our time, not even a peaceful family dinner.

***

This summer, the summer of Ferguson, marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It also marked almost fifty years since the filming of A Time for Burning, a cinéma vérité documentary about white people trying and failing to rise to the challenges of the Civil Rights Movement. It chronicles a burning time like ours: a time to break down, and a time to build up; a time to mourn, and a time to speak.

The film follows the story of Reverend Bill Youngdahl, a young liberal pastor at the all-white Augustana Lutheran Church in Omaha, who attempts to pursue better race relations in his community by partnering with nearby black churches to organize a series of voluntary interracial visits in church members’ homes.

Most of the film takes place in a bureaucratic world of weak coffee, metal folding chairs, and tense, interminable meetings. Heated conversations provide the drama as members of Augustana’s social ministry committee try to persuade the rest of the church to support the program. As committee member Ray Christensen says, pulling out all the stops, “If we don’t start now as a church, the world is going to pass us by on the biggest issue of our lifetime!” Getting a grudging go-ahead, the members then meet with their counterparts at the black churches to plan the proposed exchanges. But many members of Augustana are increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of fraught interracial conversations, asking “Why be so revolutionary?” and muttering about bad timing. Congregational drama ensues, expressed through the passive aggressive conventions of Lutheran niceness. A frustrated Christensen asks: “A hundred years of preaching and where has it gone? Where has it gone?”

Although the film was initially commissioned by Lutheran Film Associates to provide an uplifting example of church-sponsored interracial dialogue, reality failed to cooperate. The interracial visits never happen, and Youngdahl is forced to resign. The film ends with ironic intercut images of black and white Christians receiving Holy Communion separately at their segregated churches—the opposite of communion.

A Time for Burning was nominated for an Academy Award, called “a glowing beauty” by the New York Times, and turned down by three television networks, presumably because of its unsettling message. Set in a city that was soon to be rocked by the so-called race riots of 1966, 1968, and 1969, the film raises some of the same questions that were posed in the Village Voice and driven home by the uprising in Ferguson: What, if anything, should privileged people do about political problems that they have the option to ignore? Should they challenge each other about their political sins and responsibilities, or should they keep the peace? Are discomfort and disagreement always bad? Are other things worse?

But unlike the advice in the Village Voice piece, the answers the film offers are anything but easy. This is partly because from the beginning, A Time for Burning puts privileged people’s political disagreements in the context of the lived experience and searing systemic analysis of oppressed people of color. Prompted by the filmmakers Bill Jersey and Barbara Connell, Youngdahl crosses color and class lines to meet with black people on their home turf, and Jersey and Connell consistently juxtapose the white people’s evasive arguments about race with the rigorous critiques of informed, exasperated African Americans. As a result, the desire of many white congregants for an unruffled peace comes to seem more and more dangerous. Uncomfortable conversations take on a new urgency.

We are all familiar with movies about black people starring white people: The Help, The Blind Side, and others too numerous to name. A Time for Burning is perhaps unique as a movie about white people that stars black people. Yes, it follows the familiar story of a well-meaning white liberal, the generous, brave, and sometimes naively optimistic Reverend Youngdahl. We get to know and care about him and his staunchest allies in the church, matter-of-fact Ted and open-hearted Ray, and we meet many other white people along the way—the conflict-averse bishop who tells Youngdahl that “I don’t think it’s dishonest to be to be diplomatic—what I call diplomatic, some other people might call it cowardice”; the Great Society mayor concerned about ghettos and white flight; the radical woman who has been crusading for civil rights for years and has lost friends and hope in the process; the mildly militant members of the social ministry committee who have never had a real conversation with a black person before and would rather like to have the chance; the reactionary church council members who keep repeating “it’s not the right time.”

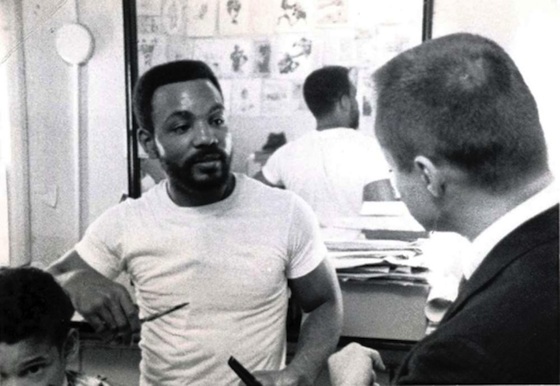

But the analysis, the conscience, the charisma, and the context for the white church’s story are all provided by black people. The precocious members of the black church youth group diagnose white people’s problems with the crystal clarity of youth—young women and men talking excitedly over each other in bursts of feeling as they deconstruct religious hypocrisy with the gospel. The leaders of local black churches try to make the case for why now is the time, or why it might already be too late: Earl says, “We’re at the point now where demonstrations don’t work anymore. You have only one choice. Race riots, or forget it.” And then there is the unforgettable black nationalist barber Ernie Chambers and the working-class men who convene in his barbershop to discuss white folks’ self-deception and the connections between racism in Omaha and wars in Korea and Vietnam. A young boy getting a haircut looks on quietly and absorbs the best political education available in America.

I keep coming back to the early scene when Youngdahl first ventures out of his comfort zone to visit Chambers, who has decorated the walls of his barbershop with newspaper pictures of the black dead in Mississippi and Alabama, of white cops in sunglasses that erase their eyes, and white men with chaw in their cheeks rejoicing in a courtroom as lynchers go free. Chambers welcomes Youngdahl with a virtuosic verbal indictment that is also an appeal, an economic and religious analysis, a warning, and a declaration of despair. He speaks with a measured calmness, fluid and cool, casually snipping his customer’s hair and occasionally gesturing with a comb, but his words burn slow like a hot coal as the sweat pours down Youngdahl’s face:

I can’t solve the problem. You guys pull the strings that close schools. You guys drop the bombs that keep our kids restricted to the ghetto. You guys write up the restricted covenants that keep us out of houses. So it’s up to you to talk to your brothers and your sisters and persuade them that they have a responsibility. We’ve assumed ours for over four hundred years and we’re tired of this kind of stuff now. We’re not going to suffer patiently anymore. No more turning the other cheek. No more blessing our enemies. No more praying for those who despitefully use us. … You’re treaty-breakers, you’re liars, you’re thieves, you rape entire continents and races of people. Then you wonder why these very people don’t have any confidence and trust in you. Your religion means nothing, your law is a farce and we see it everyday. You demonstrated it in Alabama. And I can say “you” because you’re part of the whole system. You profit from it. In fact you make your living from it. … As far as we’re concerned, your Jesus is contaminated, just like everything else you’ve tried to force upon us is contaminated. So you can have him. … I think the problem is so bad that we can have no understanding at all. … You talk about justice and it means something to you, we talk about it and it means something else to us. And it will always be that way.

Even as Chambers disavows the possibility of racial reconciliation, even as he denies a shared language of justice, he states an inconvenient truth: in a nation in which white people control the wealth and the real estate and the education system and the government, black people can’t solve their problems on their own.

It is this speech that prompts Youngdahl to reflect, “Doggone it, we did this. We did do it. We’re all guilty, terribly guilty. But what do we do now? Do we sit around and despair? If we do, then let’s all knock ourselves off and get the heck off the earth. Or do we try to live together and work out a better life?”

***

Since the protests began last month, there have been lists circulating about what white people can do. The Huffington Post suggested one thing; Dame Magazine suggested ten; The Root suggested twelve. They are good lists, though they remind me a little of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s list at the end of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, where she asks “But, what can any individual do?” (Her answers were “feel right”; pray; and make “some effort at reparation.”) The problem is that these lists have been circulating for hundreds of years. To quote A Time for Burning: “A hundred years of preaching, and where has it gone?” Or, to quote a viral sign held high by a woman marching in solidarity with Ferguson: “I CANNOT BELIEVE I STILL HAVE TO PROTEST THIS SHIT!!”

Still, lists are a place to turn when the world is on fire, and A Time for Burning has given me some resolutions to add to the long list I’m always writing for myself. I am completely unqualified to offer advice to anyone, but since I’m grateful for this film and what it’s taught me, I’ll confess my resolutions to you.

I don’t want to just “feel right” about race. In fact, I don’t want to feel right. I want to feel awkward. I want to feel the friction. As A Time for Burning suggests, healing and illuminating interracial conversations about race are a timeworn white fantasy—and even if they happen, which they mostly don’t, they can be an annoying time-suck for people of color, and falsely reassuring for white people. What’s truly necessary is for white people to have hard conversations about injustice with other white people, not gratuitous arguments but challenges that count. I once sat aghast and silent at a dinner table as a white NYPD cop who worked in the Bronx and a white millionaire who was partly raised by servants of color found common ground in jokes about black incarceration and undocumented Latinos—jokes that reflected real choices they would likely make in their lives, choices that would actually hurt people. In retrospect, their racist solidarity and my silence were all one; silence like mine is what makes this kind of lethal solidarity possible.

I want to be willing to bear some of the cost of racism, a cost that is so unevenly distributed and that is visible in rates of incarceration, unemployment, hypertension, diabetes, debt, infant mortality, stop and frisk, and death by guns. I want to bear my share of the cost not just in social discomfort but in tedium and tiredness, in my time and my bank account and my body. I love social media and t-shirts with slogans, and I think marches are energizing and photogenic, but I believe the battle is also being fought in the meetings that no one has time to go to: in school board and city elections, in voter registration drives, in budget debates and hiring decisions and referendums on the minimum wage. I want to show up when showing up is the last thing I want to do. I want to believe the battle is being fought in the hours I spend with my students trying to help compensate for the often segregated and unequal public school system. I want to believe it is being fought in how I choose to spend my days off and what I pray about and what I write about, and whether I write.

I want to be unafraid of failure, and I want to redefine failure. This is not a struggle that will ever be over. Just as there is an unbroken line from Emmett Till to Michael Brown, there is an unbroken line from Martin Luther King, Jr. to the woman who can’t believe she still has to protest this shit. Struggles for freedom fail only if we assume that unlike every other generation we are destined to see the end of the bent arc of the moral universe. After getting kicked out of Augustana, Bill Youngdahl proceeded to protest the Vietnam War, start an urban studies program at a Lutheran college, and work for justice for LGBT people in the church. Ernie Chambers has served in the Nebraska State Senate since before I was born, and he is just as fiery and unrelenting as ever. I’m not a historical figure and I don’t matter, but I believe it is better to live in the struggle, because like those long-ago Christians in Omaha I believe that sin is real, and I believe that religion is meaningful when it says that someday I will need to give an account of what I did with the racial privilege I was randomly given at birth, and of what I did about the burning injustice I sometimes chose not to see.